E. A. Burbank-His Experiences in Painting Indian Life

By JAMES WILLIAM PATTISON

Now, Mr. Burbank, what dessert shall I order for you? They serve excellent apple pies here. No dessert; if I have to live with the Indians, the dessert habit might as well be abandoned, he replied. No doubt your fare must have been brutally bad. Not always; I was recently taken in by an Indian family, living in a stone house at a distance from any village, and they treated me beyond description well, all kindness and fine food; in fact, better food than most white people around there have, and it was cooked by the mother of the family, too. But this state of affairs must be recent; a short time back the Indians had no sort of civilization. True, but do not forget the Indian schools where housekeeping is carefully taught to the girls. The house was of two rooms, earth floored, and the children shared the space with the varied live stock about the place. However, they were delightfully attentive and thoughtful. Your cruel Indian is mild and tenderhearted he has confidence in your integrity and admires the things you can do. But you must have submitted to much rude fare and lodging when you found them living in tepees. There is no tepee life any more. The Indians are but little nomadic in these days. Each family has its house, built perhaps of stone, possibly of sods, more frequently of adobe; and they stay in one place, farming and raising some stock, and they wear store clothes, though most of the old chiefs have their savage costume laid away against ceremonial days, a snake dance and the like. They paint themselves only on such special occasions.

And do the chiefs still hold despotic sway over their tribes? Possibly; those who once were medicine men have the greatest influence. They are becoming too civilized to have chiefs. Some one of them is governor, made so either by appointment or through his abilities, and it is not necessarily a lifelong service. The governor regulates the civil matters of the tribe; the medicine man continuing, as of old, to influence them through their superstitions.

But it should be known that the number of tribes is almost beyond counting, frequently a tribe numbering but a handful of individuals. I found one tribe of exactly two persons, a man and a woman, and they were not husband and wife, which will soon be extinct, of course. Generally speaking, only the large and conspicuous tribes are known to us. These numerous little-tribe governors were a great nuisance to me. The men whom I wished to paint would not come to me, so I had to go to them; traveling long distances, mostly on horseback, when necessary on foot, and then I had to lug my painting kit. Of course I carried influential letters to Indian agents and army officers. But when I arrived at one of these little outlying villages, the governor would want to know what I was doing there; usually roughly ordering me out, and to make no delay in my going. Many times I managed to persuade them that I was big chief in my own country, and succeeded in pleasing them with my pictures, though the pictures sometimes betrayed me because of superstitions and prejudices. It was useless to protest when the governor still insisted on showing his authority, and I retreated to the nearest village store. Though the distance might be considerable, they were sure, sooner or later, to gather about the store, and I could waylay those whom I wanted as they came in to trade. In course of time the difficulties were overcome, and the freedom of the country was granted me.

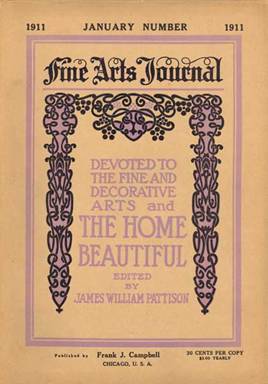

CHIEF BEN CHE DEH (NAMBE)

By E. A. Burbank

Courtesy Moulton & Ricketts

Mr. Burbank has a very striking face and square jaw; is a sample of the man of force, and still very tactful and diplomatic. He looks as if he could always get what he wanted. He has not always painted Indians.

He fell into it by accident, and did his work so well that he found immediate patronage, and has prospered thereby. He was born in 1858, and has his home in Harvard, Illinois, not far from Chicago. In his early days he studied with the primitive institution in Chicago which has now become the Art Institute, the instructors being that coterie of ancients who are now advanced in years or already called to the other side. He has a very distinct talent for still life painting, being able to render every minute detail in an object, with force, exactness and beautiful finish. Finding opportunity, he spent a term of years at the academy in Munich, in the midst of conditions which promoted exactness of observation, good drawing and attention to detail.

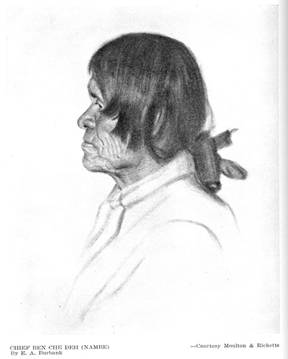

APACHE (NAVAJO)

By E. A. Burbank

Courtesy Moulton & Ricketts

Probably no school could have been more suited to the development of Mr. Burbanks talent. One of his amusements, while in Munich, was to make numberless sketches, with pen or pencil, of the quaint corners and architectural groupings about the old Bavarian capital; and on coming home he found that this collection was extensive and remarkably interesting. Quite naturally he turned his attention to portrait painting, executing beautiful pictures mostly of cabinet size. Of course they were exquisitely finished, and the color most acceptable. One of the important portraits of this period was that of his uncle, Edwin E. Ayer, who is shown sitting in an easy attitude in an arm-chair, at his feet a bright red Indian cushion, and surrounded by his extensive collection of

CHE-BE-TAH (NAVAJO)

By E. A. Burbank

Courtesy Moulton & Ricketts

Americana, which is one of the most complete in existence. The collection of Indian relics is now at the Field Museum; other objects are at the Newberry Library. In the portrait, the very brilliant Navajo blankets are much in evidence, and the entire canvas is filled with beaded buckskin hunting bags and other objects, contrasting blues and yellows and reds, besides the Indian pottery and baskets. The picture is very brilliant and much admired. Mr. Burbanks studio was decorated with a most extraordinary number of picturesque objects brought from Munich, and was one of the famous show places for the entertainment of out-of-town visitors. Quite naturally, inasmuch as he spent so many years in Munich, where genre pictures - that is, those giving the story of domestic life -prevail, he looked about him for American subjects, and discovered in the negro the most interesting material that the locality afforded. These genre pictures were all painted in cabinet size, the heads as large as a moderate-sized apple.

PEE-LEY (MOQUI)

By E. A. Burbank

Courtesy Moulton & Ricketts

Perhaps the most popular was the American Beauty, a negro boy of excellent complexion, burying his nose in a large American Beauty rose. A dark green coat and the green foliage of the rose furnish an excellent contrast with the colored boys skin. Mr. Burbank had no end of curious experiences with these young citizens, and the newspaper reporters found the situation exceedingly fertile material for their facetiousness. The Yerkes prize, offered annually at the exhibition of the Chicago Society of Artists, fell to Burbanks picture, His Favorite Amusement, a colored youth playing a banjo.

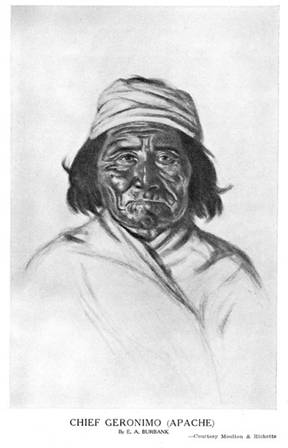

The pictures of negro life brought him much admiration as well as financial reward. About this time Geronimo, the wily medicine man who had given the United States army such long continued trouble, was a conspicuous figure on the frontier, although his fighting days were over and he was a somewhat indulged prisoner at Fort Sill. Burbank was on his way South to study negro life, but he was commissioned by his uncle, Mr. E. E. Ayer, to visit Fort Sill and secure the portrait of Geronimo. This resulted in two months work, two likenesses of the medicine man, as well as a number of other noted Indians, and made a great friend of Geronimo. It was this ability, on Burbanks part, to secure the confidence of these savages; and the accuracy of his likeness, as well as the absolute rendering of all the costumes, armaments and trinkets, which made the Indians declare that he was Big Chief. Although Geronimo was dressed in white mans clothes, he arrayed himself for the occasion in some of the finery with which he had made himself glorious. One of these portraits is in the Field Museum. From Spokane Mr. Burbank wrote telling of the difficulties he underwent to secure a portrait of Chief Joseph. From Spokane I had to go eighty miles by cars, and then hire a rig to ride thirty-eight miles aver the roughest and rockiest of roads; had to crass the Grand Coulee; cross the Columbia River in an Indian canoe, and then travel twelve miles on horseback, with paint box and accouterments strapped to the horse. Chief Joseph lives in the mast secluded place at the Nes Pilem sub agency. Most of the Indians, including Chief Moses, had gone three hundred miles away to pick hops, but fortunately Joseph was there. It took him a day to make up his mind to sit. At last I got him to put on his war paint and costume, and I got a good portrait of him. He was the best sitter I ever had; he sat so still that he tired himself out, and announced with a deep sigh that he would never sit for another portrait. He accompanied me on my return fifty miles back to the railroad station, and I became well acquainted with him. He is full of fun, joked a good deal, and gave the most amusing account of his trip east.

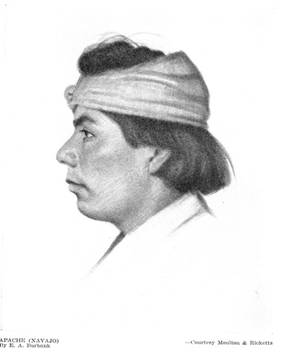

CHIEF JOSEPH (NEZ PERCES) By E. A. Burbank

Courtesy Moulton & Ricketts

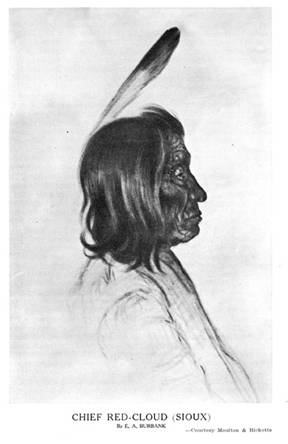

In another letter he says: I have been among the Sioux Indians at Fart Yates, and got a portrait of Rain-in-the-Face. I traveled eighty miles by wagon to get him. This Indian took a prominent part in the Custer fight. I painted a Sioux squaw, and a Sioux Indian in war costume. I was disappointed in the Sioux at Fort Yates, as they are so civilized hardly one has an Indian costume; but they tell me that, at Pine Ridge, I will find that the Sioux wear their native dress a good deal. At a place called Ditch Camp, seventeen miles from here, I saw the Crow Indian war dance. It lasted four days, and was the finest thing I ever saw in costuming. There were five hundred Indians, nearly all of them naked excepting breech cloths, with the body painted all over with different colors. Some of them would be painted green, with their bodies tattooed. I painted one of them in dance costume. I also painted a portrait of Curley, a Crow Indian, who was Custers scout, and the only one who got out of the fight alive. All the Indians here (four hundred of them) were in the war dance, and all have fine costumes; and these I am painting. I have fixed them up as if they were in the dance. The Indian I am painting now is naked excepting breechcloth; his body is all painted, including face, a bright vermilion red, and his face is tattooed blue. There are blue stripes down his arms and legs. Then, he wears feathers dyed a beautiful green. He also has on fine moccasins. Another Indian paints his body a pea green, and has ornaments to match. This is a very quiet place to work in, twenty-five miles from a railroad, in the mountains, and the mail comes three times a week.

I came very near not being able to have the Crow Indians sit for me. When I first got here, they saw one of my pictures in an unfinished state, and said the reason it was not finished was because the Indian wouldnt sit, he having heard that I took the picture east and threw poison on its face, and the Indian here, one thousand miles away, drops dead the minute the poison touches the canvas. Mr. Campbell, who has an Indian store here and speaks Crow fluently, told them he had known me for years, and I had always been fair and square and proved myself his friend. He said he would not allow me to stay on the place if I did such a thing, and that it was not so. But it is true that I take the pictures east and sell them to people who like Indians. The Indians believed him; so everything is all right now.

Mr. Burbank says: Do you know why Indians paint? I thought they did it to look pretty; but they dont, though some of the women do, but the men paint when they know an enemy is coming. They say it is medicine, and a ball or arrow wont hit them. An Indian always paints himself the same way; every streak of paint meaning something. A certain mark means that he has stolen a horse; and that is virtue, as he only steals from his enemies. Red paint always means blood; the man who has been in a hand-to-hand conflict will dip his hand in red paint and make the print on his breast. Here is a picture of White Swan, Renos trusted scout - he was just as faithful as anyone who ever lived; he told Reno they would all get killed, but hed stay by him. He was left on the field for dead, cut in the forehead with a tomahawk, wounded in the right hand, and shot in the leg. For each wound he wears one feather dipped in red paint. The red rings about his arms are for the Sioux he has killed; the yellow ones, for the Cheyennes. If you spent one evening with Chief Joseph, youd love him, you couldnt help it. He is one of the nicest men lever knew. When I made this picture, it was the first time he had posed for a portrait with his face painted, and he made me keep the doors and windows locked. It took four days, and he gave a sigh of relief when it was over. They sit so still that it is perfect torture. I told him, when I got through with the eyes, that he neednt sit so still, that he could go to sleep if he wanted to. But he scorned the idea of such a thing. Burbank says of these Indian friends, that they are a lot of awfully nice murderers.

There is the same variety in progress towards civilization to he found among the Indians as among white men. A very large number of the chiefs whose names are familiar to us have adopted white mens customs, and externally resemble the whites in manners and dress, whatever may be in their hearts. Chief Keokuk is seventy-four years old, lives in a fine, comfortable house of four or five rooms, and it is as neatly kept as that of any white woman. He dresses neatly, and keeps his shoes carefully polished; all probably because he is a devout Christian, of the Baptist persuasion, and one of the important men who lead in prayer every Sunday. He is the son of the old Keokuk, whose name was given to the well-known Iowa city. In painting his portrait, I found that he had a profile remarkably like that of Henry Ward Beecher. At the time of the Blackhawk war he was a boy; but he has so excellent a memory that his anecdotes of the conflict are intensely interesting. His wife, who at the time of the war was a little child, escaped across the Mississippi River, on the back of her swimming mother. The artist abiding in this neighborhood could find no lodging excepting at the Eagle Hotel, at the Sac and Fox agency, which is six miles from the nearest railway station, Stroub, Oklahoma. The agency is rich, with three general stores, one drug store, two blacksmiths shops, the hotel and several agency buildings. The so-called hotel is old, rickety and entirely innocent of paint. It rejoices in a hanging sign outside; but this is such a handy thing to shoot at that the lettering is pretty well wiped out. The poor widow who manages it has to have a deal of courage; the meals are not so very bad but pork is about the only meat in use. The rooms are unendurable, with no furniture at all except the bed, with its excessively dirty bedclothes. There is but one sheet and a pillow case long ignorant of the washtub. The institution pays well because many pass through here, mostly Indians who are but little disturbed by the condition of the sheets. A few nights since the place was crowded with drunken Indians, who were whooping it up and giving their war cry. Just before supper the landlady asked me if I had any objections to sitting at the same table with the Indians. I answered no; that I had dined with Indians before; but when I saw the condition of my companions, I did object, to myself. However, they behaved themselves well, considering the condition they were in. Later on, as I came in to go to my room, they noticed me, and asked me to join their party; they were all drunk, and drinking some white-looking liquid, and seemed to have plenty, as I noticed quart bottles protruding from their pockets.

Mr. Burbank is a most interesting conversationalist, full of anecdotes about his Indian friends, and he tells about Chief BurntAll-Over, a Cheyenne with a fine record as a fighter, and a face covered with every line that could zigzag across it. This Indian described the method of scalping an enemy. Sometimes only a little scalp lock was taken; on other occasions the whole scalp was removed. So he went through the motions of drawing a knife around the head, placing one foot on the dead mans shoulder, grasping the hair in both hands, and jerking the scalp from the bone, imitating the sounds of the coming away of the skin with a plook.

Mr. Burbank says that the Moquis are thieves. At one time they found a bottle of medicine which they liked. Whenever they took a swallow of it they would make good the space with water, and so they continued drinking until the bottle contained nothing but water. One day he discovered paint on an Indians hand, and thus discovered who had been stealing his colors. In lecturing him about it, he told the Indian that the paint was bad medicine and would kill him. So he got rid of it at once, and stole no more paint.

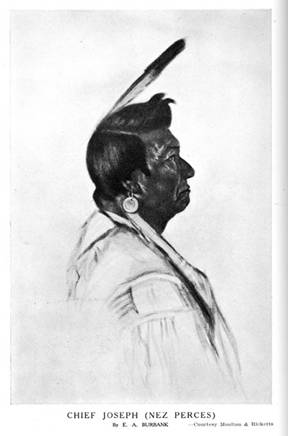

CHIEF GERONIMO (APACHE)

By E. A. Burbank

Courtesy Moulton & Ricketts

He induced Geronimo to tell the story of his life. The old Indian said the first thing he could remember was seeing Indians doing a war dance around a fire at night. Geronimo was full of jokes of very simple kind, and was fond of poking fun at the Indian who was a model. It does not sound very funny to us, but seemed to entertain these childlike spirits. Turning to one, he would say, Comanche no good; and the reply would come back, Apache no good, Apache like squaw. Then Geronimo would say, You no good as five cents. On another occasion a little son of a Kiowa who was posing for Burbank became noisy in the studio. After several cautions by his father, to which he paid little attention, he was quieted by the reproach, My son, you will break my heart if you do not obey me. This was sufficient, and the child sat still during the remainder of the sitting.

When asked how he persuaded the Indians to pose, and if it was by flattery, the artist jingled two big silver dollars together, declaring that flattery was good, but that the jingle of the silver had more effect. He seems to have established a regular tariff, so much for a plainly dressed Indian, and more for one in war dance costume. Sometimes all your money and all your prayers fail to bring them out in ceremonial dress. When It-Say-Yo posed in costume, we locked the doors, and rubbed soap over the windows, so as to make the glass opaque. Commonly there was such a crowd of dark-skinned faces at the window that the light was obstructed. If It-Say-Yo had been discovered by his friends, they would have flogged him seriously. He is an Indian of awful aspect, with nose and cheeks striped across with black, green, yellow and red; his legs and body painted in zigzags of green; and a pure white spot on his forehead. Many strings of shell and turquoise beads are twisted about his thick neck. His shield bears the eagle emblem, marking him as one of the seven Chiefs of the Bow. However, this great warrior is now humbly and peacefully washing dishes and doing other menial work for one of the traders. He is an exceedingly nice fellow, said Burbank, even though he did kill his wifes mother.

CHIEF RED-CLOUD (SIOUX) By E. A. Burbank

Courtesy Moulton & Ricketts

Chief Plenty Cows, the principal chief of the Crows, is described as being gorgeous to the extreme. His costume is the finest in the possession of any Indian; one hundred weasel skins are used in its ornamentation, and these were presented by Mr. Weare of Chicago, who also gave Plenty Cows a gold watch. The Crows named the Chicagoan Bald Eagle, so that watch bears the inscription From Bald Eagle to Plenty Cows. Plenty Cows is the proudest human being met in the country, and he walks about with the dignity of a king. With his squaw and Indian valet he drove one hundred miles to meet the artist in his studio. Hours were consumed in making his toilet, with the assistance of the squaw and the servant. Soaked with sugar and water, to make it stand on end, his hair was arranged a la pompadour. His face was painted red, and his forehead white. Besides the weasel skins, his costume was ornamented with mare than thirty scalps fastened with porcupine quills. After the completion of his attire, it took him fifteen minutes to finish his admiration of himself, and he then demanded of the painter that he hold a hand mirror until he could please himself with a pose. After a while he was satisfied, and called out, Go ahead. His valet sat behind the painter in order to keep him informed on what part of the portrait the artist was busy. If told that a certain part of his costume was being studied, the Indian would smooth out all the wrinkles, and readjust the ornaments. He was very satisfied with the painted face; but the white feather in his hair, being partly in shadow, displeased him, and nothing would do but to make the shadow white. Then it was pronounced Heap good. Of course the shadow on the white feather had later to he painted in again.

Of all the numberless portraits of Indian chiefs, none is perhaps more important than that of Chief Joseph, unless possibly that of Geronimo. Joseph was a man of wonderful character, a keen strategist; and, had he been in command of a great army, would have been a great general. The intrusion of lawless whites forced him to the war path; his famous retreat, encumbered with several hundred squaws and helpless children, through an almost impassable mountain country, the United States army behind him, ahead of him and on either flank, could hardly be equaled by any general. When he surrendered to General Miles, his speech, indicating acceptance of the conditions, was so pathetic that even the veteran officers wiped away tears of sympathy. I quote from one of Mr. Burbanks letters a statement of the time and effort required to secure the attention of so important a man as Chief Joseph of the Nez Perces:

On arriving at Chief Josephs retreat, I sent for him, and he soon appeared on his horse. He is of medium height, well built, with a round face and a kind expression. He shook hands with me; and, when he learned, through an interpreter, that I wanted to paint him, he desired to think it over before answering. I had with me a portrait of Plenty Cows, of the Crow Nation, whom Joseph happened to know. He liked the portrait, and said, I know him; he nice man. I noticed him counting the strings of Zuni beads around Plenty Cows neck, such beads being scarce in the north. After finishing his counting, he said he had same kind of beads, only one more string.

After a while he consented to sit, and it was arranged that he should come in the morning. He did not put in an appearance. So, at noon, I went to his house which is in a most secluded place. His home is small, with two rooms. His farm looked prosperous. He had a fine chiefs costume, made of buckskin, beads and weasels skins. His face was painted, and the door had to be locked while he sat. He was one of my very best sitters, but tired himself out, and was glad when it was over.

He took me back to the railroad, fifty miles, with his little team of horses and buckboard. He spoke a little English, and we had a pleasant journey. At one place on the road he pointed over to a lone tree and said : You see one stick over there? Nice skookum water over there, all the time ice water, (meaning a spring.) He told of his troubles with the government, his being taken to Injun Territory, as he called it, of his children dying there, and many of his people, including some chiefs. All the time hot there; all the time hot water to drink.

He told of his visit east, where he participated in the Grant monument dedication and was the guest of General Miles and on his honorary staff. General Miles nice man, has nice things to eat. When asked what he liked best of all the things he had, he replied, warmly, Oysters, ah, so skookum, which is Chinook for excellent.

We arrived at the railroad town of Wilbur about nine p. m., where we had a good supper. In the morning he wanted me to go with him while he bought some things to take back with him. His last words were promises to sit for me for two more portraits.

Chief Joseph is a kind, good hearted man, and as reliable and gentle as can be. He is well liked by all who know him, and especially by officers who helped to force him to surrender. General Miles, in his book, speaks highly of him. His story is one of the noblest and saddest of all our Indian history.

Looking at our illustration of Chief Joseph, the cropped-off hair suggests the effects of civilization. There is another portrait of Joseph, a front face view with long hair, or something of fur to suggest the long locks, drawn in front of his shoulders; and his forehead is painted with round dots, on the right red, and on the left dark green. The profile portrait has the feather in yellow and black, with a wisp of green at the end. From behind the ears, falling on the chest, are long strips of red stuff. The blanket shows the colors of most coverings of the sort, in yellow and blue. His face is not painted.

The drawing of Geronimo is exactly the same as the portrait in color, and his hair, though very unkempt, is not the long hair of the wild Indian. There is no paint on his face, nor does he wear any ornaments. . The red band on the top of his head and the perfectly simple old undecorated red blanket are the only suggestions of savage life.

CHIEF PRETTY-EAGLE (CROW)

By E. A. Burbank

Courtesy Moulton & Ricketts

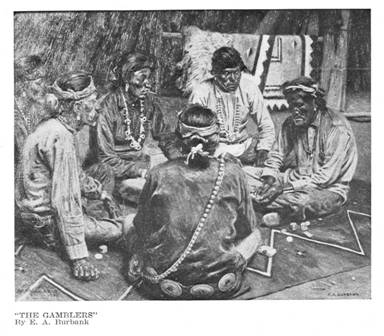

It is plainly to be seen that Mr. Burbanks special talent and Munich training have fitted him to be the one successful painter of Indians. Besides numberless portraits, the artist has painted an important picture of the snake dance. In the actual dance these Indians carried squirming snakes about in their mouths. But those who posed for the characters in this snake dance picture could never be induced to do it. So the artist substituted a roll of cloth, in order to secure the play of facial muscles.

THE GAMBLERS

By E. A. Burbank